In this week’s blog, I want to address the issue of common mistakes that artists make when signing their artwork. The first thing you need to understand is that any mark you make on your artwork is part of the piece of work you are creating. The size, colour and placement of your signature is an integral part of that work. The size, style and placement of the signature matters, and you need to get it right.

So, here are a few ‘rules’ you need to remember, starting with the most important. You really must sign your work. To leave it unsigned is a huge mistake. Your signature identifies the work as yours. It doesn’t matter if you are at the beginning of your art journey, and perhaps you know the work isn’t that good yet and that in one, three, five or ten years from now it will be better. Be proud of your achievement at this time and let the world know that this is where you started. Be proud of where you are in your journey. Own that point in your journey. Sign it.

As well as identifying you as the artist, your signature should complement the work and not detract from it in any way. If you are new to all this and you haven’t settled on a particular style of signature, don’t worry. You will figure that out over time.

Ideally, you should sign the front of the work. The normal place to sign a painting is at the bottom right hand side of the work. It’s the place people expect to see it. There could be a good reason for not placing it there and choosing a different placement, but in all events, you really should sign the front.

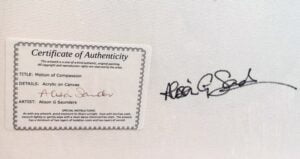

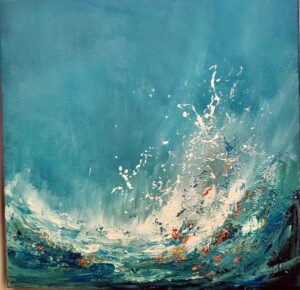

There are painters (and I am one of them) who sign the back of their works. The reason is that being an abstract painter not signing the front allows the buyer to hang the work whichever way round they like best. Signing the back and, if practical, also attaching to it a certificate of authenticity ensures that the work can be identified as yours.

A note here, though. Certificates and stickers can fall (or be taken) off so make sure you sign the back with a permanent marker of some kind. Your signature can get covered up when a painting is framed, which isn’t a huge problem if you attach a certificate to, and sign the back, too. However, never sign the frame or mount, for the obvious reason that if the work ever needs re-framing or mounting, the signature will be lost forever.

If you are looking for alternative ways to make your mark on your work you could consider having a stamp of your initials or logo made which you use on the front or back. However, signing the front is still considered to be the best option.

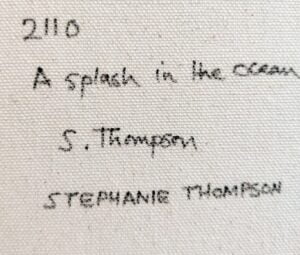

As your art journey continues, the quantity of work you have produced increases and documenting it becomes more difficult. So try to get into the habit of documenting and numbering your work right from the start; it will pay dividends in the end.

The best practice is as follows:

Your signature, mark, stamp or monogram should be somewhere on your work;

The rest of the information can be recorded on the back of the canvas and in your record book; and

You need to include your name (the one you use to identify yourself as an artist), the title of your work, the reference or inventory number – start at ‘101’ or ‘1001’ – it just looks better than starting at ‘1’ – and the date the work was completed.

Signatures are as varied and as individual as people. Artists are too, without exception. Give some thought to choosing how you use your signature to identify your work.

I was advised by one elderly art tutor not to use my full name because women in art are not considered to be as worthy as men and using my initials rather than my full name (similar to the way many female authors – still – use a male nom de plume) would allow the work to be judged solely on its merits and not by any views about gender.

Having noted that, I think the world has moved on a bit, and I now proudly include my first name. However, I also realised that I need to include my middle initial as when Googling [other search engines are, apparently, available – Ed] my name, Alison Saunders, Google brings up first the British barrister and former Director of Public Prosecutions. By adding the ‘G’, I now come up first, which is clearly where I want to be. It is worth considering things like this when you start out on this journey.

Also, whilst the simple use of your initials is probably the easiest identification to execute, you could decide, as I have, that it is preferable to use your full name.

I have seen some beautiful Japanese-style symbols made into a brass stamp and set into wet paint as a recognisable and consistent mark, just as people used to have their own ‘seal’ to press into hot wax when securing envelopes and scrolls. Of course, if you work in different sizes, some large and some small, you may need to adapt your signature to the respective size of the work.

I have a series of small drawings on paper in which I effectively hide my initials in the work along with the date, but in this case, I also sign the work on the back, too.

The point is that your mark needs to be recognisable and consistent.

In my early days of using watercolour a lot I once produced a piece as a reference for a printmaking project. I grabbed a felt pen and wrote my signature across the piece and it looked dreadful. The light colour of the watercolour paint overlaid with a heavy black marker meant that the painting became about my signature and not about the subject matter, which is clearly where I wanted the focus to be.

Making your signature too big for the piece is yet another common mistake. Your signature should not dominate, either in strength of colour or size. Whilst your signature is part of the work, you do not want people to be distracted by it.

Finally, there are always exceptions to any rule and here is no different. One very important reason that you should not sign a piece of your artwork is copyright!

It is a common practice for students to copy other painters or use photographers’ photographs in order to learn techniques and perfect their craft. It is something which is even encouraged.

If you visit the National Gallery in London’s Trafalgar Square, you will often find artists and art students copying great master works. By copying work, you really, really see the way work has been made. It educates and informs your future practice, but it is not your work. If a teacher supplies photos in classes for you to copy, it is their work, not yours.

So, to avoid upsetting teachers, other artists/photographers, here are the rules.

If you copy a painting or photograph produced by someone else, your outcome is not an original work. If you then sign that work it becomes a breach of the original artist’s copyright and can be legally considered to be a forgery.

Someone I know told me recently that photos supplied by a teacher but painted by her did not constitute a problem as she had produced the paintings, therefore it was her work and she did not have to worry about copyright. She could not have been more wrong!

The photographs were the artworks, which had been copied. The rules are clear. This person argued with her teacher when challenged and, despite being told not to, proceeded to sell the work at an art fair and did very nicely thank you very much.

Of course she did. The supplied photographs had been cropped and enhanced in order that the outcome of the student’s classwork was of a high standard. However, the copyright still belonged to the teacher as she supplied the photos, not the student.

In this instance the teacher decided not to do anything more about it, but another teacher might not be so generous. You have been warned.

If you have enjoyed reading this post, please like and follow me and share it with people who you think might be interested. I am always looking for new artists to feature and if there is a subject you would like me to write about, I will be happy to consider it. Sharing, liking and following my blogs increases the number of people the algorithm shows them to. If you check out my website you can see my class bookings are now online too.

Thank you in advance for supporting me this way.

1 Comment.

Thank you this was very informative I will now go back over my mothers artwork to see how consistent she was all those years ago.